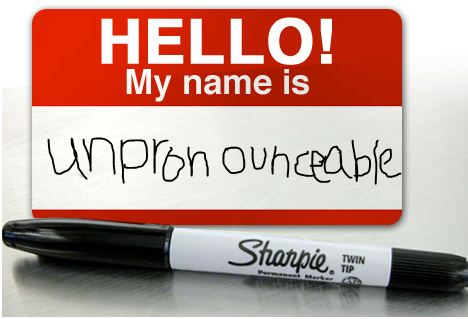

Unpronounceable — why can't people give bioinformatics tools sensible names?

Okay, so many of you know that I have a bit of an issue with bioinformatics tools with names that are formed from very tenuous acronyms or initialisms. I've handed out many JABBA awards for cases of 'Just Another Bogus Bioinformatics Acronym'. But now there is another blight on the landscape of bioinformatics nomenclature…that of unpronounceable names.

If you develop bioinformatics tools, you would hopefully want to promote those tools to others. This could be in a formal publication, or at a conference presentation, or even over a cup of coffee with a colleague. In all of these situations, you would hope that the name of your bioinformatics tool should be memorable. One way of making it memorable is to make it pronounceable. Surely, that's not asking that much? And yet…

- GO2MSIG, an automated GO based multi-species gene set generator for gene set enrichment analysis – This is not so hard to pronounce (go-to-em-sig), but it is a little awkward and not very memorable.

- AbsCN-seq: a statistical method to estimate tumor purity, ploidy and absolute copy numbers from next-generation sequencing data — I guess this only has one obvious pronunciation (abs-see-en-seq), but again not particularly memorable.

- QCGWAS: A flexible R package for automated quality control of genome-wide association results — This sort of works if you separate out the two commonly used initialisms (QC + GWAS), but maybe not everyone will spot this straight away (especially if you are not familiar with GWAS). I still find this a bit of mouthful to say (cue-see-gee-was).

- CMGRN: a web server for constructing multilevel gene regulatory networks using ChIP-seq and gene expression data — The lack of vowels means that can only ever be pronounced by uttering every consonant separately (see-em-gee-ar-en).

- iNuc-PseKNC: a sequence-based predictor for predicting nucleosome positioning in genomes with pseudo k-tuple nucleotide composition — I don't know where to start with this one! Imagine that you had to spell this out to a journalist over the phone (something that can happen in science!): "The software name? Yes, it's aye (lower-case), en (upper-case), you-see (lower-case), hyphen, pee (upper-case), ess-ee (lower-case), and kay-en-see (upper-case)…hello, are you still there?".

- MFSPSSMpred: identifying short disorder-to-order binding regions in disordered proteins based on contextual local evolutionary conservation — Couldn't be simpler really. I look forward to telling my colleagues about em-eff-ess-pee-ess-ess-em-pred.

- mRMRe: an R package for parallelized mRMR ensemble feature selection — This is not as long as some of the others, but trying saying this five times fast (em-ar-em-ar-ee).

- LoQAtE—Localization and Quantitation ATlas of the yeast proteomE. A new tool for multiparametric dissection of single-protein behavior in response to biological perturbations in yeast — I get the feeling that this is meant to be pronounced 'LOCATE', but that's only a guess. Maybe it's really pronounced low-queue-at-ee? It's clumsy, ugly, and also an incredibly tenuous initialism.

- HoPaCI-DB: host-Pseudomonas and Coxiella interaction database — This, like many of the above entries, also featured as a JABBA award recipient. This is not as bad an acronym/initialism as others, but it ranks highly for its lack of obvious pronunciation. Is it ho-pa-cee-aye-dee-bee, hop-pah-cee-aye-dee-bee, ho-pa-sigh-dee-bee, or even ho-pack-ee-dee-bee???

There is a lot of bioinformatics software in this world. If you choose to add to this ever growing software catalog, then it will be in your interest to make your software easy to discover and easy to promote. For your own sake, and for the sake of any potential users of your software, I strongly urge you to ask yourself the following five questions:

- Is the name memorable?

- Does the name have one obvious pronunciation?

- Could I easily spell the name out to a journalist over the phone?

- Is the name of my database tool free from any needless mixed capitalization?

- Have I considered whether my software name is based on such a tenuous acronym or intialism that it will probably end up receiving a JABBA award?